I designed a new 30-minute workshop for students this semester called “See through the internet: 8 questions & answers about how the internet really works.” I’ve given it a total of 1 time so far, to 2 people, today, but am scheduled for several more later in the semester. The subject matter is close to my heart, though, so I look for any opportunity to share this material. Perhaps you’ll find it useful, too. Here’s a draft summary of the workshop curriculum. Note that it is aimed as an intro for undergrad students.

I designed a new 30-minute workshop for students this semester called “See through the internet: 8 questions & answers about how the internet really works.” I’ve given it a total of 1 time so far, to 2 people, today, but am scheduled for several more later in the semester. The subject matter is close to my heart, though, so I look for any opportunity to share this material. Perhaps you’ll find it useful, too. Here’s a draft summary of the workshop curriculum. Note that it is aimed as an intro for undergrad students.

Download handout as a PDF or just read below.

—

See through the internet

8 questions & answers about how the internet really works

- When is “the cloud” not a cloud?

- How does a website get to your computer?

- Who owns a website?

- Why do you and I see different search results?

- Who does Google think you are?

- Who’s tracking you?

- How do you browse anonymously?

- Have you been hacked?

—

When is “the cloud” not a cloud?

All the time. What we think of as a wireless, wispy cloud is in fact made up of a vast network of wires, servers, hubs, and buildings. When you access your email or Dropbox or other cloud-based services, your computer is sending a request for files from another physical computer that lives somewhere else in the world.

Further watching: Bundled, Buried & Behind Closed Doors: video tour of network hubs and discussion from experts

—

How does a website get to your computer?

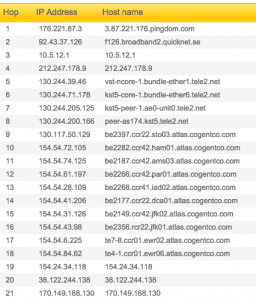

Pick a website and copy its URL. We’ll use nytimes.com here as an example.

On a Mac: Open Terminal (search for the program) and type traceroute nytimes.com

On a PC: Open Command Prompt (Start menu » All programs » Accessories) and type tracert nytimes.com

Browser option: Go to tools.pingdom.com/ping and choose traceroute (it’ll be testing from Pingdom’s computers, though, not yours). Type in the URL and submit.

Traceroute will show you all the routers (internet connector points) your computer must contact to request to access a webpage. It’s tracing a map across the city, or even the country, or even the world as your request travels from router to router to find the server (special computer) that hosts the website (stores the website’s files). Think of it like a highway that connects many cities: if you’re driving from San Diego to Seattle, the highway doesn’t go straight there — it also runs through other big cities like L.A. and San Francisco, because traffic is more efficient that way.

Each router or server will display an IP address, the numerical address that only that machine is assigned. So “nytimes.com” is actually just a human-readable version of the real web address for the New York Times, which is 170.149.172.130, a computer that is probably downtown. In between your computer and nytimes.com, there are many other IP addresses. Using some internet sleuthing skills, you can find out where these IP addresses are located geographically and/or who owns them.

When to use this: Use traceroute when you want to visualize how far away a website is, or when you want to diagnose whether a website is not loading because of a problem with your network, the website itself, or somewhere in between.

Further reading: Seeing Networks (NYC edition): a visual guide to the physical network in New York City

—

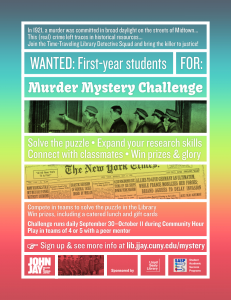

Our desired learning outcomes were basic research skills (finding books and articles) as well as team-based learning and gaining familiarity with the study spaces and friendly staff in the Library.

Our desired learning outcomes were basic research skills (finding books and articles) as well as team-based learning and gaining familiarity with the study spaces and friendly staff in the Library. With the invaluable help of Student Academic Success Programs (SASP), we arranged coveted prizes for the top three teams who answered accurately and most quickly: catered lunches in the Faculty Dining Room, $20 Amazon gift cards, $10 Barnes & Noble gift cards, and New York Times tote bags and travel mugs.

With the invaluable help of Student Academic Success Programs (SASP), we arranged coveted prizes for the top three teams who answered accurately and most quickly: catered lunches in the Faculty Dining Room, $20 Amazon gift cards, $10 Barnes & Noble gift cards, and New York Times tote bags and travel mugs.