I get asked often what it is I do, exactly, and I still don’t have my elevator pitch down pat. I usually choose to view that as a good thing, because I value the freedom to explore new territories and direct my own projects. However, a few recent reads have given me pause, and I’m rethinking my approach to my job as the new semester looms.

But first, a general look: what are other emerging tech librarians doing?

Duties & skills

At the end of April, IFLA published a paper by Tara Radniecki titled “Study on emerging technologies librarians: how a new library position and its competencies are evolving to meet the technology and information needs of libraries and their patrons.” It’s a quantitative attempt to answer the question of what people with that title do, know, and wish they knew. Radniecki compares job ads to survey responses with interesting results. A few insights from her paper, which is certainly worth a read, interspersed with my unsolicited personal opinions:

- 41.8% of job ads cite reference as a duty; 72% of librarians reported doing reference work. Similarly, 38.8% of job ads cite info literacy and instruction as a duty; 61% of librarians reported doing instructional work.

- This aligns with my own experience as an ETL. I never took a reference or instruction class for my MLIS, assuming that I wouldn’t be doing traditional librarianship. Although my job’s description didn’t mention reference/instruction, I’m at the reference desk a few hours a week, and in fact I really value it — otherwise I might not work with students face-to-face at all, which would be a terrible place to start when designing systems and interfaces for them.

- 23.9% of job ads required skills/experience in social media, web 2.0, and outreach.

- I’m surprised it’s not a higher percentage. I’m of the opinion that all librarians ought to be familiar with social media. Look, this time last year, I would have rolled my eyes at this — it’s such an old buzzword by now — and yet I’ve seen too many academic people/departments fail to grasp online social etiquette.

- 94% of librarians surveyed said they needed additional skills in computer programming and coding, versus only 16.4% of job ads requiring those skills and 10.4% preferring them.

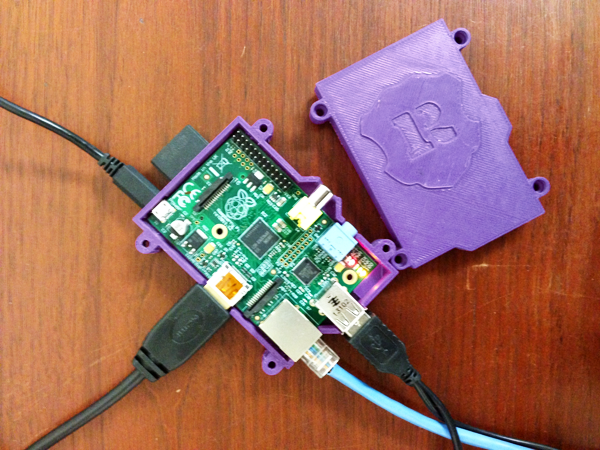

- Yes. I came into my position with years of web experience but minimal programming skills. One thing I’ve enjoyed is the impetus to get up to speed on web tech, Python, and code libraries I might not have otherwise had reason to, but it can be rough playing catch-up so much of the time.

Still, looking at numbers and general duties, it’s hard to see what ETLs do. As for me, some of my projects are the usual deliverables — design/upgrade/maintain library website, for example — and others are more playful, like tinkering with Arduino. (You can see a quick summary of my first year’s projects here.) So what exactly are others up to? I suppose that’s what discussion groups, online networks, and excitable conversations are for. And in fact, CUNY librarians, the first Emerging Tech Committee meeting of the year is coming up!

Tech criticism

“Librarian Shipwreck” wrote a long-ish response to Radniecki’s paper in a July blog post entitled, “Will Technological Critique Emerge with Emerging Technology Librarians?” (h/t Patrick Williams). The post is pretty prickly, and sometimes unfair, and its metaphors abound — but here’s one choice quote that I’m 100% behind (after the first clause):

But for the ETL to have any value other than as another soon-to-crumble-levy against the technological tide, what is essential is that the position develop a critical stance towards technology. A stance that will benefit libraries, those libraries serve, and hopefully have an effect on the larger societal conversation about technology. […] A critical stance towards technology allows for librarians to act as good stewards not only of public resources but also of public trust.

This summer has thrown the imperative of technology criticism into sharp relief for me. At the EMDA Institute, we spent a few days examining how EEBO came to be, perhaps best described in an excellent upcoming JASIST article by Bonnie Mak, “Archaeology of a Digitization.” As a room well-populated with early modern scholars, we thought we knew what it was, but after talking about its invisible labor (TCP), obscured histories (war, microfilm), and problematic remediations, we were struck by how EEBO is just one relatively benign instance of a black box we might use daily. What does it take to really know where your resource comes from, and why it is the way it is?

Moreover, the summer of surveillance leaks is exacerbating our collective ignorance of and anxieties about the technologies we rely on every day. I suspect few of us are changing our web habits at all, despite the furor. I talk about it daily, yet I struggle to understand what’s really going on — let alone how I should respond professionally. Originally, I viewed my function at John Jay as a maker, creator, connector of technologies. But technology is never neutral, and I’m starting to see pause and critique as part of my charge, too.

Digital literacy

When our digital world works, it’s beautiful. When it doesn’t, it’s a black box — a black hole — that can frustrate conspicuously or break invisibly. How can we, for instance, impart to students the level of digital literacy required to understand how a personalized search engine works and how it might fail them, when it so frictionlessly serves up top results they’ll use without scrolling below the fold? Marc Scott penned a popular July blog post titled “Kids can’t use computers… and this is why it should worry you.” I won’t summarize — you should read it. Twice.

Librarians have taught students information literacy for a long time. While knowing how to spot a scholarly resource from a dud is essential, understanding systems is now equally necessary, but harder to teach — and harder to grasp, too.

______________________

So there’s where I am: trying to understand the ethics of being an emerging technologies librarian; overplanning making things and delivering on projects; prioritizing instructing students, colleagues, and peers about things I struggle to comprehend or explain; simultaneously expecting myself to embody a defensive paranoia and a wild exploratory spirit.

It’s kinda old, but the tips still work! I did some googling when I had a minute to find out if they offered that posters for downloads, and lo and behold, there’s a whole trove of educational material from Google. Their ‘lesson plan search‘ page has a handful of posters like the one above.

It’s kinda old, but the tips still work! I did some googling when I had a minute to find out if they offered that posters for downloads, and lo and behold, there’s a whole trove of educational material from Google. Their ‘lesson plan search‘ page has a handful of posters like the one above. The PDF (2 MB) prints out to 17×22 inches.

The PDF (2 MB) prints out to 17×22 inches.

![[Posted by a student] “Study time #in #library #John #Jay! Some #research #yay #instastudy #instamood #ufffff!”](https://emerging.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2013/09/studentpic3-300x181.png)

![[Posted by a student] "Can't focus on reading Aristotle it's so confusing my head hurts #lifeofacollegestudent #geeklife"](https://emerging.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2013/09/studentpic2-300x181.png)